At the back of the shop there is a door, and behind the door there is a desk, and at the desk sits a smiling man. His hair is yellow, thin like a baby’s, and his eyes are green.

The deal he offers you is this.

The world you know is going to disappear soon—you can already feel this—but he can take you to another one. You will have to give up everything you have in this world, but in that other world you can have it all back, and more.

Behind the desk there is another door. All you need to do is to walk through it. But if you are coming, you have to come now.

* * *

The shop was not designed to look quaint.

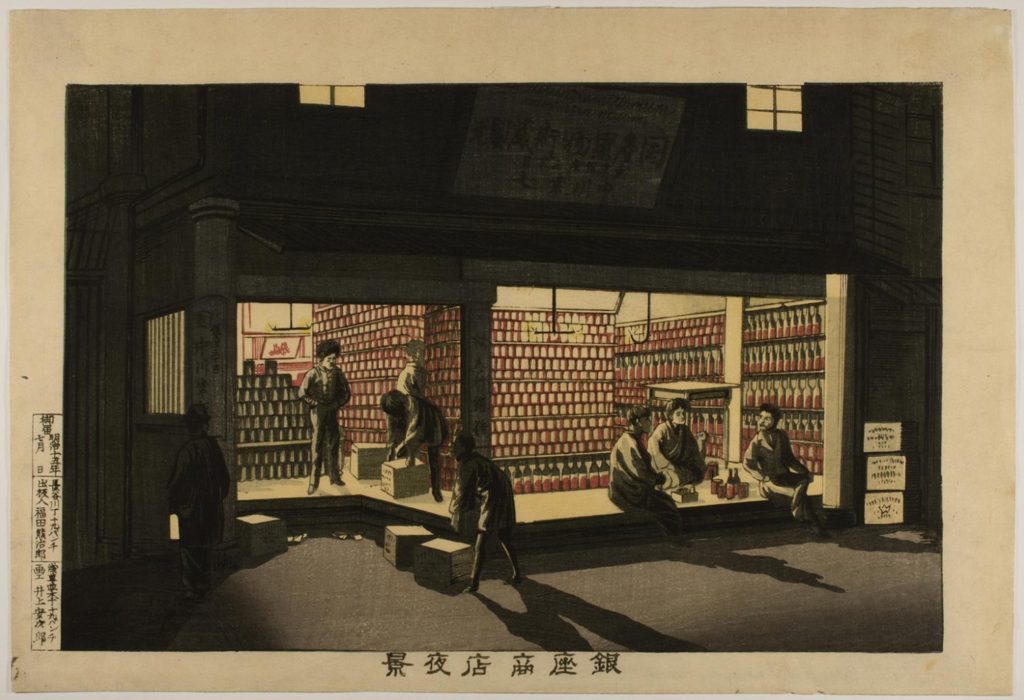

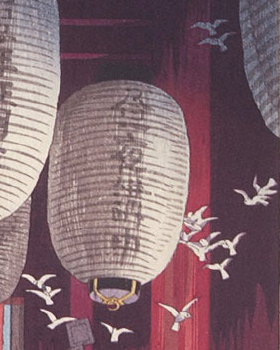

Nighttime in Ginza, Tokyo, 1882 or earlier. Light streams from an open storefront, the interior stocked with row upon row of gleaming red bottles. Three figures, sitting, appear to be sharing drinks, while others stoop to unload crates. Yet the shelves are so full and carefully arrayed that it’s hard to imagine any of the goods are for sale. It seems less like a store than a showroom for some scarcely imaginable future.

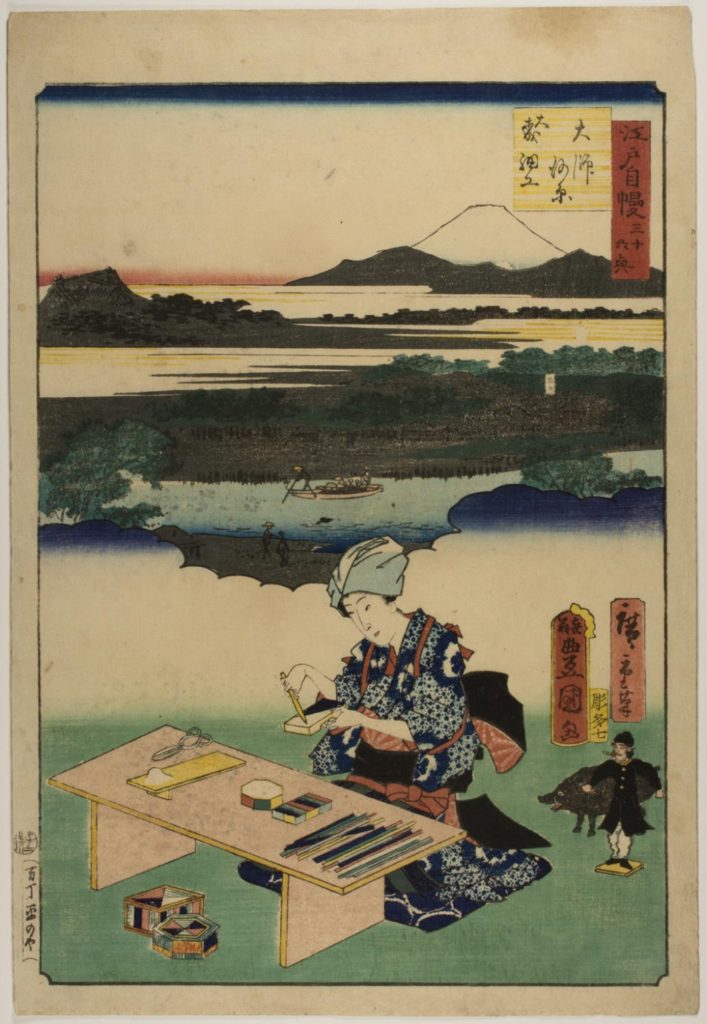

The print, by Yasuji Inoue, is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, part of a 2001 bequest by Warren and Mary Watanabe. Another copy was given to the Honolulu Museum of Art in 1959, by the writer James Michener. In 1882, the date of the image, Mary’s parents, Sataro Ishimoto and Umeyo Taketa—immigrants from Japan, called issei, the first generation—would not yet have been born.

Another print from the Watanabe bequest, by Shiro Kasamatsu, is set on a Ginza street half a century later. Now the elegant crowds seem to have arrived from that future, with a sophisticated bearing that lends their Japanese and Western period attire an almost postmodern timelessness, and you can feel the promise of spring, winter’s chill gradually lifting away. These could be extras in a sci-fi film, yet the warm yellow of the electric light, fading the night’s shadows blue and purple, washes over the scene like nostalgia. By 1934, the date given in the print’s title, Mary’s parents had long since arrived in California; Sataro was dead, leaving Umeyo and their US-born children—the nisei, or second generation—to make a life for themselves in the new world.

The image in the Kasamatsu may be dated 1934, but the work was not produced until after the war. Another print in the bequest, by Takeji Asano, makes the diminished conditions of postwar Japanese life under U.S. occupation explicit. In Night Scene of Street Stall (Yomise), a woman holding an infant crouches under the glare of a bare light bulb, as other shadowed figures stoop and huddle around them. The term yomise refers to a stand or shop that appears at night, and in this case, according to the notes prepared for a recent exhibition in Philadelphia, the draw for these tired-looking women and children must be black-market goods. It is 1949. Fortune had taken another turn by this point, for Mary and Warren, who were completing their doctorates at Harvard and Columbia, respectively. Soon, they would get married and take up research positions in Philadelphia—a young professional couple with a bright future.

* * *

“When I was a young woman in Japan,” said the grandmother to her grandchildren, “a black bird came to me in a dream. He had flown to my village all the way from California with a piece of paper in his beak. When he dropped it at my feet, he did not stop to rest. He only stretched out his great black wings and swung around, so he could hurry back to America.

“When I picked up the paper and saw it was a photograph, I was not afraid, because I knew that this was the picture my mother had shown me of the man I was supposed to marry. Except the man in this photograph was much older, and more stern in his expression. I only recognized him by his long face, and the line of his nose.”

She reached out and traced the line of her granddaughter’s nose, while her grandson watched. “And that is why I was not surprised,” she said, “when your grandfather came to meet me in San Francisco.”

“Did you fall in love with the picture in your dream?” asked the boy.

The old woman smiled, and hugged him close, squeezing his arm. “Do you feel this? How solid is this flesh? That’s how you know how much I loved.”

The girl looked down and touched her own arm. “Where is grandfather now?” she asked.

“You were at school when the FBI men came,” the grandmother said. “This was right after we had learned that Japan was at war with America.”

“I remember,” said the boy.

The old woman’s face grew more serious, and she leaned in closer. “When they went to his room, he was not there,” she said. “All they found was a pile of black feathers.”

She drew out a small envelope, removed two long black feathers, and handed one to the girl and one to the boy. “Take this feather, and always keep it safe,” she said. “As long as you never lose it, the two of you can never be separated.”

* * *

I never met Mary Watanabe, whom I only know through research. She was a biochemist first, the author, for example, of a study of “Mitochondria in the Flight Muscles of Insects.” Later, she was a language teacher and translator, and a leader of local and national social service and nonprofit organizations. But I first came across her name through her research on the early Philadelphia issei.

Japanese migrant laborers began arriving on the West Coast in significant numbers in the late 1800s, and gradually put down roots as farmers, clearing undeveloped land and specializing in crops, like strawberries, that took advantage of their agricultural expertise and acceptance of difficult working conditions. But the few Japanese who came through Philadelphia earlier weren’t issei at all, properly speaking. That is, they would not have thought of themselves as a first generation, because they did not intend to settle down in the new land, and unlike the laborers—who, at least in dreams, held on to a vision of home long after the world they left had been swept away—their privilege lent solidity to their dreams of return. Even when they would be realized only beyond death, as was true for the exile Tatsui Baba, who died at 38 in 1888, and whose remains are divided between two graves, in Philadelphia and Tokyo.

A minor historical figure in the modernization of imperial Japan, Baba was an intellectual of a political variety typical to his era—he studied law in England, organized intellectual societies there and in Japan, and lectured and published on politics and international relations. In his time, these were socially transformative, even subversive activities. Finding himself on the losing side of some political infighting, he left Japan for Philadelphia, and reoriented his activism towards efforts to shape Japan-US relations by addressing the Japanese and US people directly.

Truth is, I don’t know Japanese political history well enough to situate Baba’s politics, which seem classically liberal, but with hints of both elitist moderation and principled radicalism, and nationalist, combining admiration for the West’s political ideals with a fierce critique of its imperialist encroachment on Japan. Admittedly, I’m more interested in Baba as a character—the gifted foreign student in the centers of global power, akin to the great black intellectual W.E.B. Du Bois, or the Philippine national hero José Rizal; the stubborn man of letters, whose uncompromising streak gets him kicked out of two countries (he seems to have left England on bad terms, after a duel); the unfortunate exile, whose activism is always fractured by the uncanny intuition that the world he has lost may never be regained.

Who was Tatsui Baba, to Mary Watanabe? Did she seek a pattern or message in the fragments of the lives of these early migrants? Her comments on Baba are briefer than mine, merely taking note of the learned society he founded in Philadelphia—the Oriental Club, which survived until 2016—and of his grave. Like Baba, Mary Watanabe knew how to build an organization (I suspect she was better at it), and saw a concrete political interest in cultivating the American public’s awareness of Japanese culture.

But perhaps, in the end, what Baba made of his life was less important to her than his grave. The physical presence of it: a lonely obelisk, with his name and age and date of death in Roman characters at the base, under a long column of kanji. A marker, in historic Woodlands Cemetery, the Japanese writing and oddly foreign name announcing a presence—our presence—dating back to when the issei first began to cross the Pacific. We were here! the grave says. Yet the core of that presence is an enigma, a turning away, for the marker seems to be addressing its distant counterpart, in Yanaka Cemetery, Tokyo.

It is in the nature of belonging to be fashioned around loss, around the silhouettes the dead make as they turn their gaze away from the living. The shape of that enigma calls out to you: Enter! For no world in which we were here is ever truly lost. Except, of course, for the world you have just left behind.

* * *

This storefront thrumming with light.

* * *

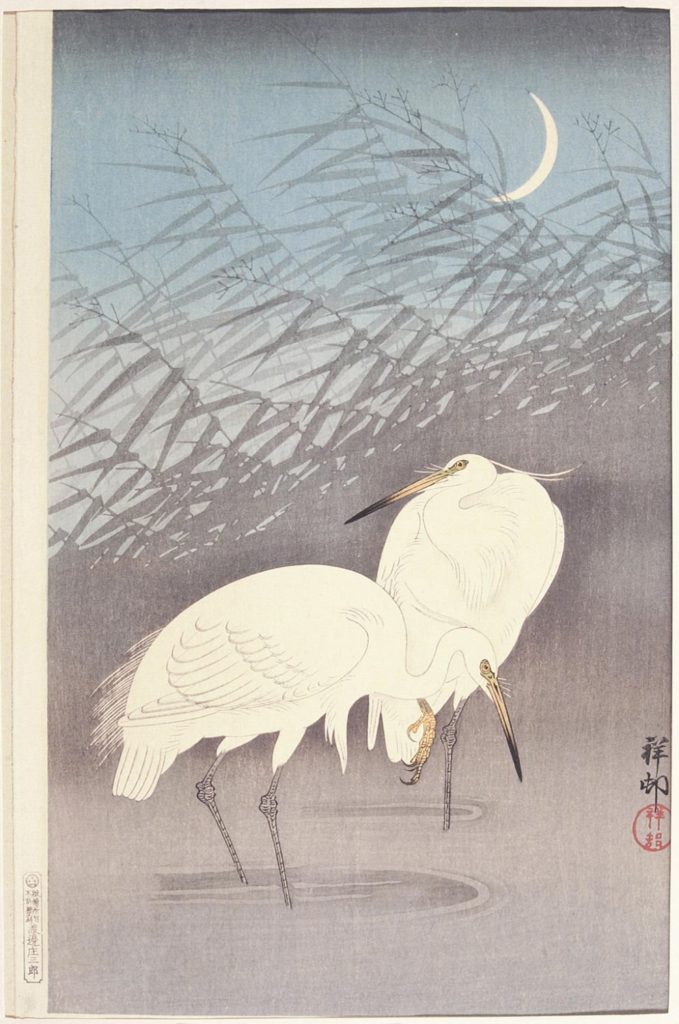

When Japanese first began crossing the Pacific for work in the late 19th century, most followed a pattern of dekasegi immigration: unable to earn a satisfactory living in a society undergoing dramatic changes, they planned to stay in the new country temporarily, just long enough to earn enough money to restore the lives they’d imagined for themselves back home. A person who immigrated in this way was called a dekaseginin; they were also referred to, more poetically, as birds of passage, or wataridori. How poetic, how delicately singing, are the names of the most desperate, unfortunate conditions, those one hopes to avoid at all costs.

Eventually, caught between the anti-Asian violence and racist laws of the US, and the willingness of Japan to disregard their wellbeing when it conflicted with national interest, they began calling themselves kimin, an abandoned people. Eventually, the term would be remembered was issei—the first generation, meaning the ones who came to stay, put down roots, raise new generations in the new land. No longer would they make a home for themselves in the wind, chasing and being chased by the weather. Their children, the nisei—citizens, with access to all the rights that entailed!—were the proof of their belonging in the new land. Until the day they learned that, without whiteness, their rights as citizens were like feathers scattered by a storm.

* * *

Reading Mary Watanabe’s writing on the early Philadelphia issei is what led me to research her own extensive work with the local Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) chapter, and to find images of the artwork she and her husband collected. I began, a bit obsessively, to piece together details of her life from publicly available records—birth and death dates for her, her husband, and her parents; immigration records, census entries, records from camp. I found Sataro’s World War I draft registration card, and those of Warren and her brother Hideo, from World War II; the record of Umeyo’s naturalization in 1957, after the repeal of racist laws barring the issei from citizenship; and an index entry suggesting that she and Warren were married in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1950.

I cannot claim to know what Mary Watanabe lost. Her father died around the age I am as I write this; she was less than a year younger than my daughter is now. Camp was still, for them, almost a decade and a half away. In 1942, Mary graduated from San Jose State, with bachelor’s degrees in chemistry and biology. Her degree, with highest honors, was mailed to her residence in the horse stables at Santa Anita racetrack, where she and her family were detained while a permanent camp was built for them at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Her fellowship for graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin was cancelled, but with the help of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), she went to Radcliffe instead. She took a doctorate in biology and worked as a biochemist with the Army Quartermaster Corps in Philadelphia.

Her camp records list her primary occupation as “Maids, General,” with a potential occupation of “Chemists, Assayers, and Metallurgists.” Her mother was also listed as a maid, with no other potential occupation. Nor was one listed for her brother Hideo, whose primary occupation was put down as “Farm Hands, Fruit,” with a secondary occupation of “Farm Hands, Vegetable.” No current or former occupations were given for her sister Fumiye, then around sixteen. In the archives of the War Relocation Authority (WRA)’s resettlement program, there are photographs of a smiling Hideo at the Wallrath Greenhouses in Waltham, Massachusetts, and one of Umeyo and Fumiye—now Carol—laughing on a Cambridge garden bench. Carol would spend over four decades as a librarian at Harvard, where an award would be established in her honor.

In Philadelphia, Warren had a long career as a researcher in industry. Mary’s professional life was rather different; according to one account, after her marriage she became a “housekeeper.” By the mid-1950s she was back in school, studying Japanese language at Penn, where she continued on as a lecturer. In 1968, a magazine profile in the Philadelphia Inquirer celebrated her new job, translating Japanese research for the benefit of US scientists, and caught her and Warren in a faux-candid snapshot—just two hard-working PhDs sharing their “office-at-home.” (These were the days when the accomplishments of overachieving nisei and their sansei children were being celebrated in the national press, promoting a “model minority” image used to dismiss militant black protest.)

Later, Mary became the national president of the Pacific/Asian Coalition, an organization that grew out of an engagement between social services professionals and the radical Asian American movement. She was a leader in the local JACL (though a 1958 notice in the Pacific Citizen carelessly referred to a “Dr. and Mrs. Warren Watanabe”). She was the founding president of the organization that maintains the historic Shofuso Japanese House and Garden, in Philadelphia’s West Fairmont Park. I cannot begin to take the measure of what she lost and what she gained, what she gave away to others and what was never returned to her.

In West Coast communities before the war, nisei men typically complained that the only job they could get with an advanced degree was selling fruits and vegetables at a produce stand. For a highly educated nisei woman, then, the prospect of being a housewife—of doing the unpaid labor of a household supported by a husband’s single income—surely sounded better than adding a maid’s paid domestic labor of on top of it.

Yet among Mary’s mother’s generation, the issei, wives were often better educated than their husbands, and than other women in the new world. Many issei were “picture brides,” named for marriages arranged by transpacific correspondence. Issei grooms were notorious for sending photos younger and more handsome than their owners, and for inflating their wealth or class status. For most issei women, the new land was struggle, and old dreams belonged to a lost world.

Growing up before the war, Mary must have seemed, to her mother, like a citizen of a world no one could see. But as her camp records showed, Mary had already made plans of her own.

* * *

They were fortunate that it was winter, because every day the stove would fill with ash.

* * *

After Pearl Harbor, many Japanese Americans chose to burn books and papers written in Japanese, along with other objects—photographs, wall hangings, records, even toys—that might seem conspicuously foreign to the FBI, whose agents were arresting community leaders. This scene of immolation is iconic in literary accounts of the war, like Monica Sone’s classic memoir, Nisei Daughter, and I’ve always seen it as an act of radical preservation, of commemoration against all hope, in the very teeth of despair.

To the feared FBI, these objects might appear threateningly illegible, a child’s doll no less inscrutable than a volume of philosophy, because it was race, not language, which rendered them unreadable. In the same way, Japanese Americans themselves would soon be locked up, en masse, not because they were all presumed guilty, but because of a belief that their race made determining loyalty impossible. In this context, the decision to burn the objects was pragmatic—rather than hoping to prove their innocence, the issei preferred to cast them beyond examination, forever.

Many of these objects were prized possessions—family letters, heirlooms, keepsakes from the lost worlds any immigrant leaves behind. To burn your most precious belongings is, like the cremation of the dead, the consecration of a passage to the world beyond. On this side of the fire, an object can be lost, sold, or stolen, broken or exchanged, but once it passes into ash, it is yours and only yours, until the day you yourself traverse the smoldering threshold.

Those of us born after this scene are least likely to forget it, for it describes an inheritance we will never be able to touch. What would happen if we did? Perhaps we are on firmer ground with other objects, other memories and longings. In Seattle, where I live, you can visit a tea shop in a restored hotel and gaze through a glass floor at suitcases, left behind in 1942, that were never reclaimed. At the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, a wall of old luggage separates an exhibit of historical artifacts from a portion of an actual Heart Mountain barracks.

I do not know what Mary Watanabe lost, before the war or after. The FBI taking away her father—that was one problem, at least, that her family did not have to worry about. I do know that the determination with which she pursued her postwar language studies was not typical of prewar nisei, who generally resented the added hours they spent in Japanese schools as children. How curious it must have been to discover that, in this new postwar world in Philadelphia, a love for Japanese culture connoted social status, not a racialized threat.

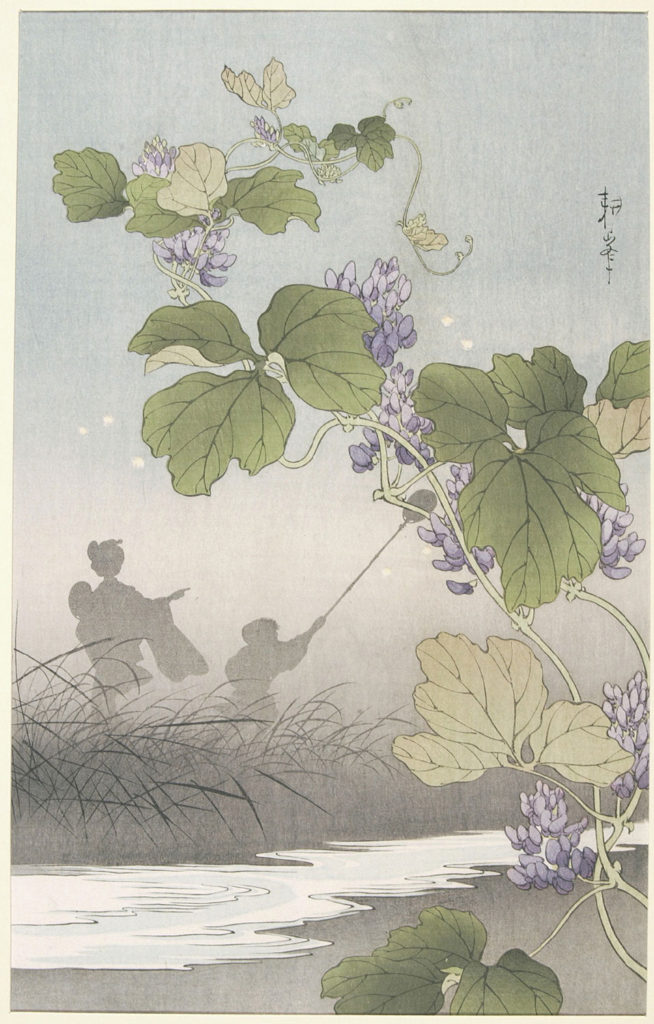

The art in the Watanabe bequest is, I assume, more expensive and of higher quality than anything that a family like Mary’s would have been likely to own, and perhaps burn, before camp. Whether or not these objects could replace whatever she might have lost, which I cannot know, they are what was given to her, and they were—are still—beautiful.

It must be said, however, that the story the images tell is a Japanese story, not a Japanese American one. For a nisei like Dr. Mary Ishimoto Watanabe, the images relate a story of the world her parents chose to leave behind, not the new world that they found.

But the story of the images is a Japanese American story. Our history is the story of the things that we have been given to take the place of everything that we have lost.

* * *

A grave that is half-emptied and thus doubled, a grave that looks to its twin on the far side of the world, can’t help but pull ghosts into its orbit, the way a spot of sunlight draws cats.

Tatsui Baba was never an immigrant, only an exile, but he became an issei in Mary Watanabe’s writing, nearly a century after his death. When an abandoned people choose to belong to themselves, they assert the power to travel across time and space.

As an issei he remained an exile, for the world he had lost was the same one the issei had left behind. Neither an issei nor an exile is a bird of passage, a condition of lesser status, even if the wataridori are defined by the very mobility these others have lost.

When the dead have forgotten all interest in the world of the living, and have flown, what fills the space that remains? How long did it take, after death, for Tatsui Baba to surrender his name to the stone? And who is this lonely girl you see playing in its shadow?