Wataridori Documentation Video 2019 from Rea Tajiri on Vimeo.

For me, it’s a wet winter afternoon in Seattle, and I am watching a video by an Afghan American artist, Gazelle Samizay, on display in the storefront gallery of the county arts agency. Fear of a government roundup of Muslims brought Samizay to California’s Owens Valley, to the site of one of the U.S. concentration camps that held 120,000-odd Japanese Americans during World War II. My shadow is a word writing itself across time, her video is called. Am I only the shadow conjured by her bad dreams?

Through her eyes I’m in Manzanar, staring at a string of origami cranes in impossible sunlight, heaped against dry, weathered wood. Then I’m back in gloomy Seattle, in a neighborhood once known as the Lava Beds, or Skid Road. The gallery is in a building named for a legendary Japanese American hardware store, dating back long before the war. The family that ran the hardware store was incarcerated at Minidoka.

I look up the last owner’s name on search engines, old newspaper archives, databases of people held in camp. How many men share this name? Scattered online are stories of people who met him in his later years—woodworkers, craftsmen, hobbyists—strangers who sat and listened as he patiently explained how to cut, how to sharpen, the simplest and most profound knowledge of the tools he’d surrounded himself with for a lifetime.

There’s more than a hint of Orientalism in these stories, of the Yoda-and-Luke variety, but I’m mesmerized anyway. He kept the store going long after it left the building named for his family, eventually reducing it to a specialty business run from his home—just a twenty-minute walk from where I live in south Seattle. Maybe I’ve walked by him in the neighborhood. The clues I’m finding to his early life are the stuff of novels. How many men share this identity? All I can find him talking about are tools, and how to use them. He seems to know more about saws than anyone I know knows about anything.

He still has a website, which seems inactive. The design is elegant, black text centered across a wide white page, and monochrome images of saw blades and handles. There’s a phone number, an email address, but I’m afraid to try them, afraid to break the spell.

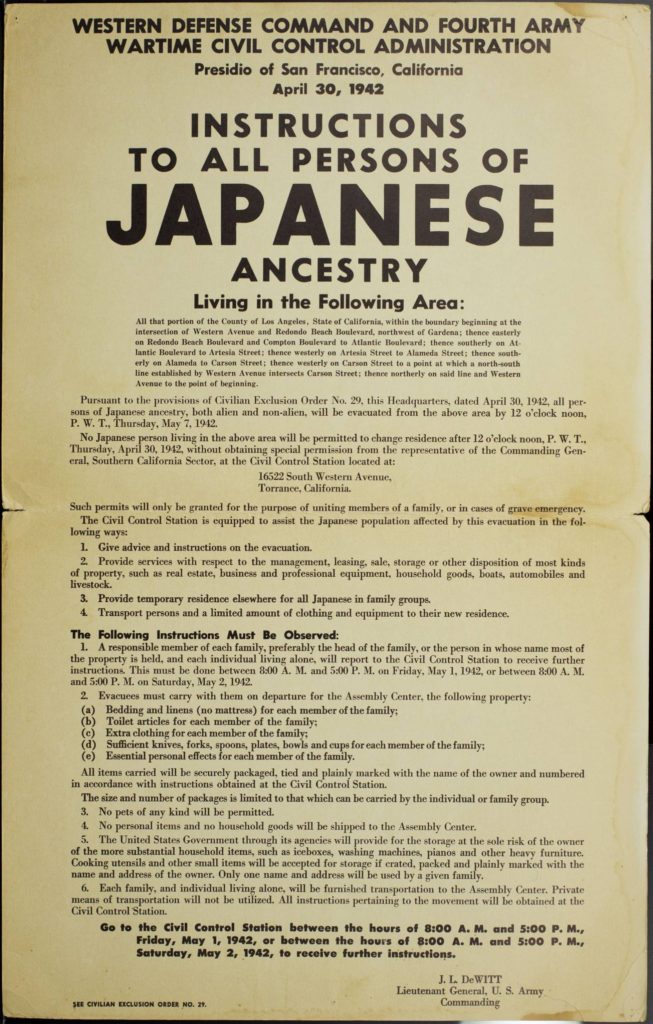

The website is literally the ghost of his shop, floating in the digital ether. The objects hang on my computer screen like the treasured possessions of the dead, like the magical charms of spirits, or like the heirlooms and keepsakes burned or buried by Japanese American families, in the narrowing days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, as they waited for the rough knock at the door of an FBI agent come to claim their father. Or like the blunt, black-and-white placards announcing the time and place of their departure from the lives and the world they knew. Instructions to all persons. Alien and non-alien.

If my fingers could grip the wood, trace the steel, would I find myself lost in another world? And would I ever be able to come back?